|

Sheffield Steel Cette voix immense qui ressurgit épisodiquement du fin fond de l'oubli : celle de Joe Cocker, une fois encore ressuscité après tant de petites morts. Joe Cocker : casualty or chart survivor ? Despite the fact Joe Cooker had to wait until 1968, when he was 24 years of age, before achieving his first major hit, the singer is rightly considered part of the early Sixties British R&B movement. The relative lateness of Cocker’s appearance in the charts may be attributed to his unsteady temperament, which has revealed itself throughout his career in excessive drinking, periodic lay-offs and frequent comebacks and a general aura of neurotic instability. On stage, Cocker’s arms fail about, his voice is hoarse and ragged and his whole stance suggests palsy or, more accurately, a man trapped between the desperate need to express himself and the recognition of his inability to do so. Disillusion and depression have plagued Cocker’s career as he swings between a genuine commitment to rock’s expressive power and a persistent desire to exploit its commercial potential.

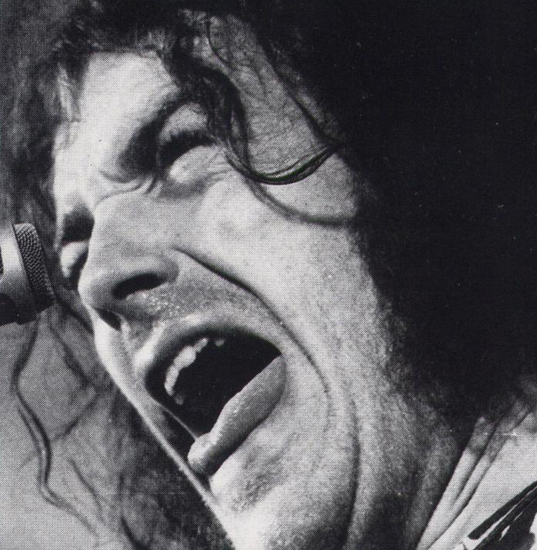

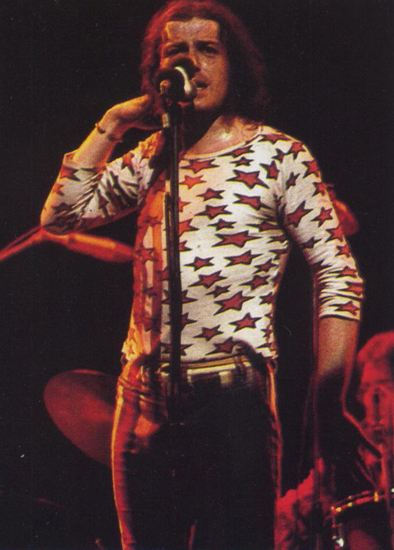

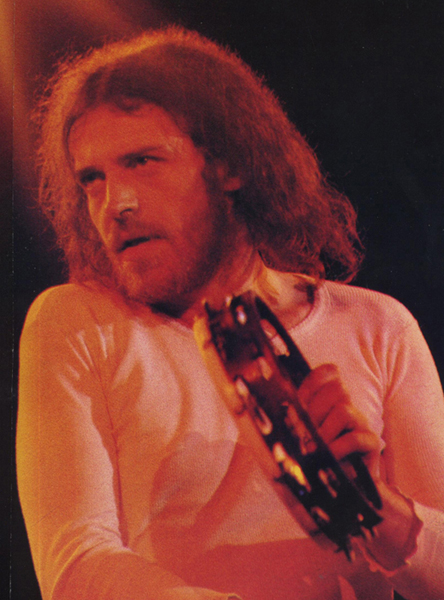

Jerking and twitching like a puppet, Joe Cocker’s shambolic stage presence (above and opposite) belied his terrific vocal energy and fair. After splitting from the Grease Band (inset opposite), his groups generally included a horn section (below).

It was commerciality which informed the choice of Cocker’s 1968 hit - a cover of the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper track, ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’ - for Cocker had been performing since the Fifties and had made his first, unsuccessful, record (as Vance Arnold backed by the Avengers) in 1963. Ironically, this debut disc was a cover of an earlier Beatles’ song, ‘I'll Cry Instead’, while the B-side was ‘Georgia On My Mind’. It was Ray Charles who had turned this Stuart Gorrell-Hoagy Carmichael standard into a US chart-topper in 1960, and it was Charles who most accurately represented Cocker’s musical aspirations. Joe Cocker was born in England’s steel town, Sheffield, on 20 May 1944. Like many other provincial centres in the late Fifties and early Sixties, Sheffield saw the rise of a musical underground based on an appreciation of black American styles. Cooker entered this underground through skiffle - a route he shared with many others, including the embryonic Beatles. ‘When we were kids, we were constantly bored" Cocker once recalled. "Then skiffle came along, Lonnie Donegan and that stuff. So when I was about 13 I bought a cheap drum kit and began messing about with some kids who’d bought guitars." By the time his schooling ended at the age of 16, Cocker had moved on to rock’n’roll and blues - working as a gas-fitter by day and playing, by night. "I was especially attracted to the blues,’ he said, ‘which seemed to have great honesty compared to all the bullshit English pop amounted to then." Feeling bluesy Ray Charles was the major influence on Cocker’s singing style, his inspiration lying in his ability to blend blues feeling with unashamedly commercial songs. By 1963, Cocker had given up his regular job and won a recording contract for Vance Arnold and the Avengers. The group toured with the Rolling Stones and the Hollies, but there was little or no interest in them and, after ‘I’ll Cry Instead’, the option on their contract was dropped. The group played American air bases for a while and Cocker recalled how they ‘went down sensationally with the blacks, and the white guys didn’t want to know us’. For the first but not the last time, Cocker’s career went into a sharp decline. He was broke, worked as a casual labourer and spent most of his money drinking. By 1967, however, the rock scene had moved on. Black music had become established ; blues feeling - transmuted by hallucinogenic drugs - underpinned much of the work of new bands then emerging and the record buying public were more open to a wider range of styles and approaches than ever before. Cocker and a pianist friend from Sheffeld, Chris Stainton, worked on some new material - including a Stainton composition called ‘Marjorine’. A demo attracted the interest of producer Denny Cordell, who had worked with the Moody Blues’, the Move, Georgie Fame and Procol Harum. ‘Marjorine’ was released as a single and entered the British Top Fifty in May 1968. The wave of interest in Cocker’s powerful style was helped along by his stage performances (with Joe Cocker’s Big Blues Band). He sang like a demented string-puppet, eyes half-closed, limbs jerking while his vocal performance possessed an energy completely at variance with his slovenly appearance. With the success of ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’, which went to Number 1 in November 1968, Cocker’s future seemed assured - anyone who could trans - form the jolly Ringo Starr-sung number from Sgt Pepper into a song of anguish and triumph had to have something. Under Denny Cordell’s guidance, Cocker now recorded his first album, "With A Little Help From My Friends" (1969) - the friends in this case being a host of sidemen including Jimmy Page, Albert Lee, Steve Winwood and Spooky Tooth drummer Mike Kellie. Following the LP’s release, a group, named the Grease Band, was formed to back Cocker on stage. The band comprised Chris Stainton, Alan Spenner (bass), Bruce Rowland (drums) and Henry McCullough (guitar) and in the early summer of 1969 Cocker and band left for America, where they played at Woodstock. Grease in the delta It was in Los Angeles that Cocker made the acquaintance of session musician-cum-producer Leon Russell, who had played on the records of such diverse artists as Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lee Lewis and the Byrds. It was with a Russell song, ‘Delta Lady’, that Cocker had his third hit - the record reached Number 10 in Britain in October - while Russell also helped to supervise the recording of a second album. Recorded in LA, Joe Cocker boasted the talents of such musicians as Sneaky Pete Kleinow of the Flying Burrito Brothers and Clarence White of the Byrds and their playing gave the album a lighter, countryish feel to the rougher, bluesy soul sound of its predecessor. This disparity in styles highlighted Cocker’s major problem : relying solely on his feeling, energy and interpretative originality, he was far too susceptible to the control of arrangers, producers and those better able to formulate a musical policy than himself. Joe Cocker’s talent was always an eccentric one and seemed unable to define and control itself. In 1970, the Grease Band - overlooked in all the high-powered session-work - left Cocker on the eve of another American tour to strike out on their own. Russell immediately stepped in and organised a group of 42 men, women and children, including the Delaney and Bonnie Band, Rita Coolidge, Cocker and Russell himself, to play the dates. The tour was billed as ‘Mad Dogs and Englishmen’ and was a huge success. A live double album of the same title was released in 1970 and a film in 1971. Cocker, ostensibly the star, emerged - so he has said - with 2000 dollars and a drug habit at the end of it, while Russell emerged as the actual star, continuing to tour with a smaller group of ‘Mad Dog’ survivors and rake in the money long after Cocker had run back to Sheffeld.

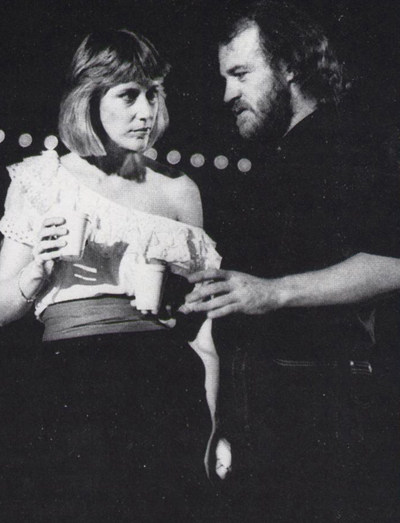

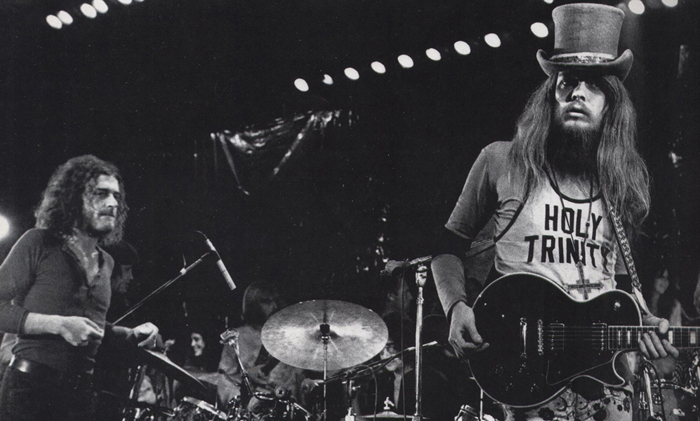

Joe Cocker might have been the offcial star of the show (above), but out in the midday sun (right) of the 'Mad Dogs And Englishmen’ tour, he found himself eclipsed by Leon R ussell (below). In 1982, however, his duet with Jennifer Warnes finally put them 'Up Where We Belong’ - at the top of the US charts.

Cocker down under The singer spent the next 18 months in virtual retirement before making a come-back in 1972 with a tour which opened in America and closed, disastrously, in Australia. In October 1972, the Australian courts convicted Cocker and six members of the tour party on drugs charges. They were ordered out of the country, but before they left Cocker appeared at one final show so drunk that he fell over, and later managed to get himself evicted from his Melbourne hotel after a brawl.

Throughout the Seventies, Cocker’s career continued to be erratic. A cover version of the Box Tops hit ‘The Letter’ had been his final UK chart entry in 1970, though he reached Number 5 in America with ‘You Are So Beautiful’ in 1975. During the decade, the singer made repeated attempts to take to live performance again, but failed signally to approach the heights of his achievements of 1968 and 1969 and although he released several albums on a variety of labels, all were marked by lack of decision and direction, uncertainty in choice of material and a shifting mass of session players. Though Cocker’s voice remained, on occasion, as soulful and expressive as ever, the arrangements, the musicians’ performances and many of the songs themselves did it little justice. By the Eighties, critics, and the majority of the public too, had written Cocker off as a wasted talent - one couldn’t help but feel that the image of a puppet or a Frankenstein monster which seemed once to counterpoint his all-too-human vocals had become ironically appropriate. But then, in November 1982, such theories were confounded when the aptly-titled ‘Up Where We Belong’ - on which Cocker duetted with Jennifer Warnes, a past collaborator with Warren Zevon and Leonard Cohen - rose to the top of the US charts. It seemed that, at last, Joe Cocker might have shrugged off his personal problems to come up trumps once again. |